Just for Teachers

- Study Guide for Teachers

- Teaching Students To Tell Stories

- How to Help Students Make Up "How and Why" or "Pourquoi" Stories

- How to Help Students Write Their Own "Noodlehead" Stories

- Lesson Plans Available for Many of Mitch and Martha's Books

- Watch Movie Clips of Children Telling Stories

- Listen to Recordings of Children Telling Stories from Mitch and Martha's Books

- Watch Animated Versions of Mitch and Martha's Books on Story Cove

- Storytelling Games

- Storytelling and State Standards for Education

- Why Use Storytelling as a Teaching Tool

- Handouts

- Updates To Mitch and Martha's Book, Children Tell Stories

Study Guide for Teachers

If Mitch and Martha will be visiting your school, use their Study Guide (PDF) to prepare students for their storytelling program. The Guide also includes numerous follow-up activities, a few of which are described below.

Teaching Students To Tell Stories

A school visit by Mitch and Martha is a terrific way to kick off a storytelling unit in your classroom, and their book, Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom , gives all the information you need to get students (and you!) telling stories. Even a one-day visit to a school can have a profound effect if teachers capitalize on the excitement generated by storytelling and get students telling and writing stories. To download a PDF file, "Why Children Should Be Given the Opportunity to Tell Stories," click here. For a list of numerous ways in which storytelling activities support state learning standards, click here. You may also find the following lists to be helpful: Sample List of Sixty Stories from our Anthologies for Third Graders to Tell and Stories from our Anthologies Categorized by Difficulty (2nd - 8th Graders).

How to Help Students Make Up "How and Why" or "Pourquoi" Stories

Use the stories in Mitch and Martha's How and Why Stories: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell as models. Everything you need to know is in Pourquoi Play: Practicing Oral Language Skills by Making up "How" and "Why" Stories Extemporaneously, a handout that you can download, along with the How and Why Story Template and the "Why Dogs Chase Cats" Story Map. And, if you wish, follow up this activity by having students write the stories down and develop them fully using the How & Why Writing Unit.

How to Help Students Write Their Own "Noodlehead" Stories

Use the stories in Mitch and Martha's Noodlehead Stories: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell as models. You can also download a complete Noodlehead Writing Unit.

Lesson Plans Available for Many of Mitch and Martha's Books

Although the focus is on K-3 for these Lesson Plans, many have information that is useful for other grade levels. Click on any of the following titles and then look for "To download lesson plans . . . "

The Ghost Catcher

The Hidden Feast

Priceless Gifts

Rooster's Night Out

The Stolen Smell

A Tale of Two Frogs

The Well of Truth

Why Koala Has a Stumpy Tail

Watch Movie Clips of Children Telling Stories

If you click on "View Video Clips" at the top of this page and scroll down, you will find several child tellers -- and more will be added in the future so keep checking back. When children hear other children telling stories, the idea of "That sounds like fun. I'll bet I could do that, too" is planted in their minds.

Listen to Recordings of Children Telling Stories from Mitch and Martha's Books

Mitch and Martha have two CD recordings, both of which include several fabulous child tellers. For details, see How and Why Stories and Stories in My Pocket.

Watch Animated Versions of Mitch and Martha's Books on Story Cove

Mitch and Martha have five books as part of the Story Cove series and all have free animated versions (including Mitch and Martha's voices) available at www.storycove.com. Although Mitch and Martha might tell some of these stories during their visit, playing the animations for students would be a great introduction. However, it is even better to show them after they have heard the story so that they have already used their own imaginations to create the story in their minds.

The Story Cove animations are aimed at primary age students but even fourth and fifth graders enjoy watching them and can be encouraged to retell them. Along with reading, writing, speaking, and listening, two more literacy skills have been added for teachers to address: "visually representing" and "viewing." After students watch Mitch and Martha tell stories, have them view any of the Story Cove movies. For example, the illustrator of "The Well of Truth," Tom Wrenn, has depicted the story the way he saw it in his mind. Have children figure out how they might tell it, or even just a part of it, using vocal and facial expression and hand motions to "visually represent" the story and help listeners visualize it in their minds.

The Hidden Feast, part of the larger and beautifully illustrated LittleFolk picture book series, also has a free animation online and will be enjoyed by K-3 students.

Storytelling Games

The games included in Children Tell Stories (pages 34-45) are perfect for classroom use, but be sure to check out the Storytelling Games section on this site as well. Students love the seven letter sentence game and it shows them that they don't need a television or a computer screen or even a game to have fun with friends -- just a paper and pencil.

Storytelling and State Standards for Education

Storytelling is the best way to help students focus on speaking and listening skills which are emphasized in both national and state educational standards. Indeed, telling stories has a profound influence on all language skills. Educator Marie M. Clay has written: "Think of how the effects snowball. The more children engage in telling stories, the more command they get over language. With more language, they can understand more detail in the stories they hear. That gives them a better idea of how stories hang together. So the better their own storytelling and retellings get, the more experience they'll bring to reading stories and writing them (from By Different Paths to Common Outcomes. York, Maine: Stenhouse, 1998, p. 40).

The following chart, "Sampling of Storytelling Activities and a Few of the State Standards They Meet" can be found in Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom. Permission is not required to link to this list, but the chart is copyrighted.

Sampling of Storytelling Activities and a Few of the State Standards They Meet:

Listening to StoriesStudents will:

|

Reading To Choose a Folktale to Tell to ClassStudents will:

|

Retelling a Story in One's Own WordsStudents will:

|

Learning a Folktale: Draw a Story MapStudents will:

|

Telling a Folktale to Various AudiencesStudents will:

|

Evaluating One's Own Storytelling and Coaching Classmates in Storytelling SkillsStudents will:

|

Making Up Stories That Include Factual InformationStudents will:

|

Playing Story Games (e.g. Fractured Fun)Students will:

|

Although State Standards vary, the underlying requirements are the same. The requirements listed here are a few of the ones we found in the Standards for many states at a wide range of grade levels.

These are samples from state standards across the United States. We found specific information for a few states on the Internet:

Florida:

www.tampastory.org/tsf_append.htm#standards

This site by the Tampa-Hillsborough County Storytelling Festival Committee includes the Florida state standards that storytelling meets.

Indiana:

http://www.geocities.com/~storiesinc/TeachersGuide.html

This "Storytelling Arts of Indiana" site contains specific activities for more than 90 English/Language Arts standards for grades 1-8. Scroll down to "Activities for State Standards."

New York:

http://www.storyarts.org/

This site by professional storyteller Heather Forest discusses how storytelling helps to meet state standards for education. Just click on "Lesson Plans" on her home page and then scroll down to "Storytelling Activities to Support New Standards for English Language Arts."

General Sites on State Standards:

Two general sites that will lead you to your own state standards are:

http://www.edstandards.org/standards.html

http://www.statestandards.com/

The following is a general statement on the importance of storytelling in the classroom from The National Council of Teachers of English.

Teaching Storytelling: A Position Statement (NCTE)

Once upon a time, oral storytelling ruled. It was the medium through which people learned their history, settled their arguments, and came to make sense of the phenomena of their world. Then along came the written word with its mysterious symbols. For a while, only the rich and privileged had access to its wonders. But in time, books, signs, pamphlets, memos, cereal boxes, constitutions - countless kinds of writing appeared everywhere people turned. The ability to read and write now ruled many lands. Oral storytelling, like the simpleminded youngest brother in the olden tales, was foolishly cast aside. Oh, in casual ways people continued to tell each other stories at bedtime, across dinner tables, and around campfires, but the respect for storytelling as a tool of learning was almost forgotten.

Luckily, a few wise librarians, camp counselors, folklorists, and traditional tellers from cultures which still highly valued the oral tale kept storytelling alive. Schoolchildren at the feet of a storyteller sat mesmerized and remembered the stories till the teller came again. Teachers discovered that children could easily recall whatever historical or scientific facts they learned through story. Children realized they made pictures in their minds as they heard stories told, and they kept making pictures even as they read silently to themselves. Just hearing stories made children want to tell and write their own tales. Parents who wanted their children to have a sense of history found eager ears for the kind of story that begins, "When I was little ...." Stories, told simply from mouth to ear, once again traveled the land.

What is Storytelling?

Storytelling is relating a tale to one or more listeners through voice and gesture. It is not the same as reading a story aloud or reciting a piece from memory or acting out a drama - though it shares common characteristics with these arts. The storyteller looks into the eyes of the audience and together they compose the tale. The storyteller begins to see and re-create, through voice and gesture, a series of mental images; the audience, from the first moment of listening, squints, stares, smiles, leans forward or falls asleep, letting the teller know whether to slow down, speed up, elaborate, or just finish. Each listener, as well as each teller, actually composes a unique set of story images derived from meanings associated with words, gestures, and sounds. The experience can be profound, exercising the thinking and touching the emotions of both teller and listener.

Why Include Storytelling in School?

Everyone who can speak can tell stories. We tell them informally as we relate the mishaps and wonders of our day-to-day lives. We gesture, exaggerate our voices, pause for effect. Listeners lean in and compose the scene of our tale in their minds. Often they are likely to be reminded of a similar tale from their own lives. These naturally learned oral skills can be used and built on in our classrooms in many ways.

Students who search their memories for details about an event as they are telling it orally will later find those details easier to capture in writing. Writing theorists value the rehearsal, or prewriting, stage of composing. Sitting in a circle and swapping personal or fictional tales is one of the best ways to help writers rehearse.

Listeners encounter both familiar and new language patterns through story. They learn new words or new contexts for already familiar words. Those who regularly hear stories, subconsciously acquire familiarity with narrative patterns and begin to predict upcoming events. Both beginning and experienced readers call on their understanding of patterns as they tackle unfamiliar texts. Then they re-create those patterns in both oral and written compositions. Learners who regularly tell stories become aware of how an audience affects a telling, and they carry that awareness into their writing.

Both tellers and listeners find a reflection of themselves in stories. Through the language of symbol, children and adults can act out through a story the fears and understandings not so easily expressed in everyday talk. Story characters represent the best and worst in humans. By exploring story territory orally, we explore ourselvesÑwhether it be through ancient myths and folktales, literary short stories, modern picture books, or poems. Teachers who value a personal understanding of their students can learn much by noting what story a child chooses to tell and how that story is uniquely composed in the telling. Through this same process, teachers can learn a great deal about themselves.

Story is the best vehicle for passing on factual information. Historical figures and events linger in children's minds when communicated by way of a narrative. The ways of other cultures, both ancient and living, acquire honor in story. The facts about how plants and animals develop, how numbers work, or how government policy influences history - any topic, for that matter - can be incorporated into story form and made more memorable if the listener takes the story to heart.

Children at any level of schooling who do not feel as competent as their peers in reading or writing are often masterful at storytelling. The comfort zone of the oral tale can be the path by which they reach the written one. Tellers who become very familiar with even one tale by retelling it often, learn that literature carries new meaning with each new encounter. Students working in pairs or in small storytelling groups learn to negotiate the meaning of a tale.

How Do You Include Storytelling in School?

Teachers who tell personal stories about their past or present lives model for students the way to recall sensory detail. Listeners can relate the most vivid images from the stories they have heard or tell back a memory the story evokes in them. They can be instructed to observe the natural storytelling taking place around them each day, noting how people use gesture and facial expression, body language, and variety in tone of voice to get the story across.

Stories can also be rehearsed. Again, the teacher's modeling of a prepared telling can introduce students to the techniques of eye contact, dramatic placement of a character within a scene, use of character voices, and more. If students spend time rehearsing a story, they become comfortable using a variety of techniques. However, it is important to remember that storytelling is communication, from the teller to the audience, not just acting or performing.

Storytellers can draft a story the same way writers draft. Audiotape or videotape recordings can offer the storyteller a chance to be reflective about the process of telling. Listeners can give feedback about where the telling engaged them most. Learning logs kept throughout a storytelling unit allow both teacher and students to write about the thinking that goes into choosing a story, mapping its scenes, coming to know its characters, deciding on detail to include or exclude.

Like writers, student storytellers learn from models. Teachers who tell personal stories or go through the process of learning to tell folk or literary tales make the most credible models. Visiting storytellers or professional tellers on audiotapes or videotapes offer students a variety of styles. Often a community historian or folklorist has a repertoire of local tales. Older students both learn and teach when they take their tales to younger audiences or community agencies. Once you get storytelling going, there is no telling where it will take you.

Oral storytelling is regaining its position of respect in communities where hundreds of people of every age gather together for festivals in celebration of its power. Schools and preservice college courses are gradually giving it curriculum space as well. It is unsurpassed as a tool for learning about ourselves, about the ever-increasing information available to us, and about the thoughts and feelings of others.

The simpleminded youngest brother in olden tales, while disregarded for a while, won the treasure in the end every time. The NCTE Committee on Storytelling invites you to reach for a treasure - the riches of storytelling.

The source for the statement printed above is: http://www.ncte.org/about/over/positions/category/curr/107637.htm.

Why Use Storytelling as a Teaching Tool

If you would like to download a list of reasons to use the oldest educational tool in today's classrooms - no matter what the age level of your students, click here.

Handouts

In addition to the ones listed here, there are several other handouts available in the Handouts section at the top of each page of this site.

Updates to Mitch and Martha's book, Children Tell Stories

Our second edition of Children Tell Stories was just too big to fit into one book! We didn't want to use so much paper that the book would not be affordable, or include so much information that it would be overwhelming, so we have included additional information here.

About the Companion DVD

The DVD can be played on a TV/DVD player or on a computer. Tips for Playing the DVD and Printing the 25 Stories from a Computer

The DVD that is a companion to Children Tell Stories was filmed in January of 2005. The documentary filmmaker, Peter Carroll, ((Click to see his Web site),) is a longtime friend of ours. For years we talked about how film would be the best tool to document our methods of teaching storytelling in schools as a way of inspiring and teaching others to do the same. Cost was always the deterrent; making a documentary is an expensive, time-consuming task. Our editor, Darcy Bradley, believed that it would be well worth the money and convinced the folks at Richard Owen Publishers ( www.rcowen.com ). Richard Owen himself was very enthusiastic, and we owe a debt of gratitude to both of them. Although they gave us guidance, we are incredibly grateful to them for mostly trusting us and Peter to do the job.

Our greatest debt is to Peter for his enthusiasm about the project. He has a playful, childlike quality that helped the students feel comfortable with him in the room almost immediately.

Making the film clearly became a labor of love for Peter; although his contract was for a twelve to fifteen minute film, he finally had to stop himself at twenty minutes. (We know that those extra few minutes represent days of work.) Peter even took the time to hone one of his family stories and tell it to the class. His written version was kept in the class library for the rest of the year. The teacher, Karen Powers, said it was so popular that it was never on the shelf. (The story will be included in our collection entitled Scared Silly, a collection of thirteen scary "jump" stories, which will be coming out in fall, 2006.)

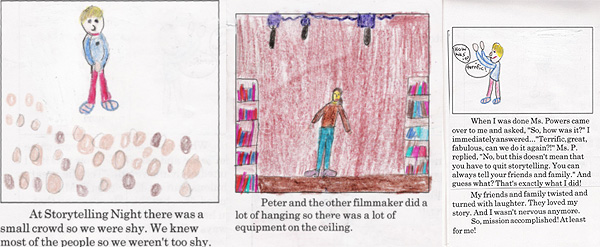

At the end, as a thank you to Peter, students wrote books about the experience of making the DVD. No one tells the story better than they do! In this section are selected pages from some of these books as well as four of them in their entirety. Reading these books from the children's perspective makes it clear that, because the camera was always on them, these students were under far more pressure than during a normal storytelling unit. Because of Peter's skill as a cameraman, and because a storytelling unit is fun and engaging, they were mostly able to forget about the camera and enjoy themselves.

The family storytelling night was clearly the hardest. There were two filmmakers, lots of lights hanging from the ceiling, and the student tellers had to wear a microphone.

We felt strongly that the film should reflect the fact that there are reluctant storytellers in every classroom. We hoped the film would show that those reluctant tellers, after conquering their fears, are also most proud of themselves at the end. However, because this was a documentary, we had no idea (and no control) over what would happen in the particular class we chose; we would simply watch things unfold as we do in any school residency. Nothing was rehearsed, including the interviews. Peter ended up filming over eighteen hours of footage, which is not unusual because the industry standard is one hour of footage per minute of film. (There is plenty more great footage and one of our goals is to get funding to have Peter do a bit longer version that could reach a wider audience, perhaps on PBS.)

Karen Powers is an incredibly dedicated and well-loved teacher who always goes out of her way to make every event special. (Not to mention that she is also very articulate, as you see on the DVD.) It has always been a joy to work in her class. For the "World Premiere" party, she made a "red carpet" at the entrance to her room. All of the four third grade classes were invited and all were given cups of popcorn for the big show. The kids had a whole award presentation planned which included opening a large envelope for "Best DVD at Northeast School." Peter was presented with a scepter and a lovely book from each child.

We are forever indebted to the parents and students at Northeast School (especially those from Karen Powers' third grade class) who were incredibly generous in their willingness to share a process that can be scary even without a camera on you at all times.

Writing How & Why Stories: A Unit for Second through Sixth Graders (PDF)

Download this seven-page document and you'll have everything you need to know to teach a writing unit on pourquoi stories.

Writing Noodlehead Stories: A Unit for Second through Sixth Graders (PDF)

Download this eight-page document and you'll have everything you need to know to teach a writing unit on "noodlehead" stories.

How to Build Curriculum Around a Story (Problems, Problems, Problems)

Because students are engaged by the world of story, they want to know more. They feel as if they know the characters and places. They will ask questions, especially if you encourage them to, which will give meaning and purpose to the activities that follow the story. We have included ideas for curriculum tie-ins for the story "Problems, Problems, Problems" (a folktale from India included on page 92 in Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom) to show you the kinds of activities stories can inspire. (All page references refer to the book.) These ideas are for many grade levels; choose the ones that are appropriate for your students.

LANGUAGE ARTS

Listening and Speaking Skills

- Go over sequence of events in the story; draw a story map

- Retell the story in a circle with each student saying a sentence

- Have students discuss the main points or theme of the story

- Tell the story as if it's a news report

- Have students conduct interviews of the characters in the story

- Have students tell the story from one character's point of view

- Do "The Mind's Eye" exercise (p. 67): have students describe one or more of the village leaders

Reading Skills

- Read the story over and over to help with the retelling process

- Read other versions of the story (See "Story Sources" on the companion DVD to Children Tell Stories for other versions) and make Venn diagrams to compare and contrast

- Read other stories from India

- Read stories with a similar theme

Writing Skills

- Retell the story in your own words; draw illustrations and publish your version (this could also be a small group activity first; then have students create individual stories)

- Write a different story with the same theme

- Write a different story with the same characters (What might have happened if people had spoken up and questioned the leaders?)

- Write a story about what happens when the people move to the new village

- Write the story in the form of a poem or play

- Keep a journal including reactions to the story and activities

- Write a letter to a character(s) in the story: for example write to the leaders as if you are a disgruntled villager

SOCIAL STUDIES

- Study the history, people, geography, and culture of India

- Show slides and photos, describe traditions and customs, and serve ethnic dishes of India

- Look for current news articles about India; display them on a bulletin board

- Find India on a map; check the latitude and longitude

MATHEMATICS

- Pretend to take a trip through India; have students add the miles from one place to another

- Make up word problems with characters from the story. (For example: Suppose the village was plagued by ten thousand mosquitoes and the villagers captured fifty frogs to eat them. If each frog ate four mosquitoes a minute, how long would it take them to get rid of the mosquitoes?)

SCIENCE

- Study the habitats of mosquitoes, frogs, and snakes

- Study the eating habits of each creature and the food chain

- Teach the scientific method: (1) Have the students ask any questions that the story brought to mind (2) Define one problem the class chooses to investigate such as which of the three creatures [the mosquito, frog, or snake] has the fastest reproduction cycle? (3) Discuss possible answers to the problem (hypotheses) (4) Discuss ways to test the hypotheses (experiments, research)

- Ecology: Use the story to demonstrate what can happen in nature when solutions are not carefully thought out

ART

- Draw a storyboard for the story

- Draw a favorite scene from the story; students can then put them in the proper sequence

- Create a quilt (made with paper) with various scenes from the story

- Create puppets, props, costumes, or scenery to put on a play of the story

- Make a diorama

- Create paper dolls for retelling the story

MUSIC

- Write the story in the form of a song or rap and perform for class

- Rewrite the story as a musical play

- Play recordings of indigenous music of India as students do artwork or physical education activities

- Make musical instruments to use while telling the story

DRAMA

- Act out the story as a play or Readers' Theater

- Create a puppet show of the story

CHARACTER EDUCATION

- Discuss the story to reinforce values such as the importance of thinking through the consequences of one's actions

HEALTH STUDIES

- Investigate diseases that are carried by mosquitoes

- Investigate "mosquito control' and how that has changed the lives of people in tropical climates

PHYSICAL EDUCATION

- Tell the story in dance form

- Have students imitate the movements of mosquitoes, snakes, and frogs as they listen to indigenous Indian music

Favorite Storytelling Links

Here are a few of our favorite storytelling sites. They will lead you to gazillions of others. We will update this list periodically so keep checking back.

www.storynet.org This site of the National Storytelling Network includes an extensive list of storytelling sites and resources. Search for storytellers, festivals, workshops, publishers, and organizations here. You will find links to sites that include the full texts of stories as well as links to many Special Interest Groups such as "Youth Storytelling" and the "Healing Story Alliance."

www.aaronshep.com Aaron Shepard is an award winning children's author whose wonderful site includes his retellings of folktales, fairy tales, tall tales, myths, legends, classic tales, and sacred stories, as well as original tales. The tales are well written and sources are always noted. Another of his specialties is reader's theater and many free scripts can be found here.

www.storyarts.org This site by professional storyteller Heather Forest promotes the use of storytelling in the classroom. She provides lesson plans and activities, discusses how storytelling helps to meet state standards for education, and recommends links to numerous other sites.

www.timsheppard.co.uk/story This site is crammed full of information for storytellers such as: frequently asked questions about storytelling, articles by Tim Sheppard and other experienced storytellers, an annotated bibliography, and numerous links.

www.pratt.lib.md.us/kids/estories The website of the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore, MD presents a variety of storytellers telling multi-cultural tales in streaming video.

www.geocities.com/storiesinc/TeachersGuide.html This "Storytelling Arts of Indiana site includes games, activities, teaching guides, and resources from various storytellers.

www.augusthouse.com August House Publishers focuses solely on storytelling books and tapes.

www.storycove.com Story Cove is an offshoot of August House Publishers. The main feature of the site is animated versions of world folktales with related activities for children/families and lesson plans that teachers can download. Book versions are available for sale but the movie versions are free online. Be sure to watch A Tale of Two Frogs: Inspired by a Russian Folktale, Rooster's Night Out: A Folktale From Cuba, and The Stolen Smell: A Folktale from Peru, all of which were retold by Mitch and Martha and feature their voices. The illustrators/animators have a great sense of humor and even our adult friends have enjoyed these stories. Keep checking back because Mitch and Martha have several more forthcoming Story Cove titles.

Storytelling Tips Booklets

The storytelling tips that appear at the beginning of each chapter in Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom were done by third graders at the end of a storytelling unit such as we describe in the book. As a form of assessment, each student made a booklet with "Six Tips for Storytelling" to show what they had learned about storytelling techniques and speaking in front of a group. For more examples of these tips, see Just for Kids.

For pictures and instructions on how to make the eight page blank booklets, see: http://www.funlessonplans.com/reading_lesson_plans/buddies.pdf. After downloading the PDF file, go directly to page 3 where you will find clear instructions and photographs to lead you through the process.

The third grade teachers at Northeast Elementary (Ithaca, NY) gave their students these directions in making their booklets:

1) What advice would you give to others about telling stories? Think about six important tips to help anyone become a good storyteller.

2) Write each tip in a detailed sentence.

3) Make an illustration to go with each tip that will make the tip even clearer.

4) Proofread your work with someone at home.

5) Do your final copy in the blank booklet.

6) The cover should include: a title such as "Six Storytelling Tips" or "Six Fabulous Tips for Storytelling;" and your name and an illustration. Use color to help grab the reader's attention.

Storytelling Star Certificate

Some teachers give their students certificates at the end of the culminating event of a storytelling unit as a tangible reminder of their hard work and achievement. You are welcome to use this "Storytelling Star" certificate.

How To Keep Current On The Best Storytelling Resources

To keep up with the best of the recent storytelling books and recordings we suggest you check the following websites for awards:

Anne Izard Storytellers' Choice Awards

www.westchesterlibraries.org/owls/awards/awards_AnneIzard_current_year.htm

This highly selective award, created to highlight and promote the art and craft of storytelling, is given to outstanding books that can be used with confidence by storytellers. The judges are librarians in the Westchester County (NY) Library System.

Storytelling World Awards

http://www.storytellingworld.com

Each year a panel of at least 50 judges with a variety of professional, personal, and geographic backgrounds selects storytelling resources and gives awards in various categories. The awards are for both books and recordings and are especially helpful because specific stories for various age levels are recommended.

American Library Association Notable Recordings

www.ala.org/ala/alsc/awardsscholarships/childrensnotable/

This prestigious award for recordings is given by the Association for Library Service to Children of the American Library Association.

Parents' Choice Awards

www.parents-choice.org/awards_portal.cfm

These awards are given by the Parents' Choice Foundation which seeks to identify the best products for children of various ages, backgrounds, skills, and interests. Awards are given to products that meet and exceed standards set by educators, scientists, performing artists, librarians, parents, and kids.

Sample List of Sixty Stories from our Anthologies for Third Graders to Tell

The following list is a sample set of stories that we might present to a classroom of third graders who would then make their story choices. We find that the process is much easier if the stories are divided into three categories according to difficulty. You can make your own lists for a particular grade level by choosing stories from "Stories From Our Anthologies, Categorized by Difficulty (2nd-8th Graders)".

Starter Stories

From Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom: The Boy Who Turned Himself into a Peanut; Excuses, Excuses; A Handful of Peanuts: Sneezy; Two Stubborn Goats on One Narrow Bridge

From How & Why Stories: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell: How Owl Got His Feathers; Why Ants Are Found Everywhere; Why Bat Flies Alone at Night; Why Cats Wash their Paws After Eating

From Noodlehead Stories: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell: No Doubt About It; When Giufa Guarded the Goldsmith's Door; Whose Horse is Whose?

From Stories in My Pocket: Tales Kids Can Tell: The Beautiful Dream; The Bundle of Sticks; The Mysterious Box; The Night the Moon Fell Into the Well; Who Will Fill the House?

From Through the Grapevine: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell: Sweet or Sour?; The Thief Who Aimed to Please

(For "Starter Stories," you can also allow students to choose from our individual picture books that are part of the "Books for Young Learners" series of Richard C. Owen Publishers. These include Tricky Rabbit, How Fox Became Red, Two Fables of Aesop, and Why Animals Never Got Fire.)

Next Step Stories

From Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom: Coyote and the Money Tree; How the Milky Way Came to Be; The Rat Princess; The Two Who Tried to Please Everyone; Why Frogs Croak When it Rains

From How & Why Stories: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell: Rabbit Counts the Crocodiles; The Taxi Ride; The Turtle Who Couldn't Stop Talking; Why Dogs Chase Cats

From Noodlehead Stories: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell: The Fool's Feather Pillow; The King Brought Down By One Blow

From Stories in My Pocket: Tales Kids Can Tell: The Biggest Donkey of All; Do They Play Soccer in Heaven?; How Coyote Was the Moon; The Mouse and the Sausage; Tilly

From Through the Grapevine: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell: Ah-Choo!; The Big, Wide-Mouth Frog; The King and the Wrestler; The Woodcutter and the River Demon

Challenging Stories

From Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom: How Brother Rabbit Fooled Whale and Elephant; The Jackal and the Lion; Why Deer and Tiger Fear Each Other

From How & Why Stories: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell: How Tigers Got Their Stripes; Two Brothers, Two Rewards; Why Hens Scratch in the Dirt; Why Parrots Only Repeat What People Say; Why the Sun Comes Up When Rooster Crows

From Noodlehead Stories: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell: The Boy Who Sold the Butter; The Donkey Egg; The Farmer Who Was Easily Fooled; Juan Bobo and the Pot That Would Not Walk

From Stories in My Pocket: Tales Kids Can Tell: Clytie; On a Dark and Stormy Night; The Silversmith and the Rich Man; The Stonecutter

From Through the Grapevine: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell: The Boy Who Battled the Troublesome Troll; The Fearsome Monster in Hare's House; Just a Drop of Honey; Monkey Gets the Last Laugh; Turtle Returns a Favor

Stories From Our Anthologies Categorized by Difficulty (2nd-8th Graders)

The following lists will be helpful to those of you who would like to do a storytelling unit where each of your students chooses an individual folktale and learns to tell it. To make student story selection easier we have listed the titles of the stories in our anthologies according to their difficulty level for specific grades (S=Starter; NS=Next Step; C=Challenging). You may choose to use these levels to steer students toward stories that might be a better fit for them, without the students knowing the levels; or you may choose to label the stories with the levels and explain what they mean to students. (For older students you may want to use terms such as "Easy, Medium, and Challenging.")

Leveling the stories is not a science. Length is only one of many determinants for the difficulty level. Some short stories would never be understood by younger students because the stories contain abstract concepts. Our leveling may seem arbitrary, and to a certain extent it is, because it depends on the experiences of individual students. It has happened, for example, that we first thought a story was easy for most third graders to tell because the first few third graders we saw tell it did so effortlessly. But as we gained more experience with the story we found many third graders weren't as successful, so we changed it to a more difficult level. Based on your students' experiences, you may also decide that a story belongs in a different difficulty level. Keep in mind that the skills of students at younger grade levels are quite different at the beginning of the school year than they are at the end, and that skill levels can vary greatly from school to school.

Levels Code: S=Starter NS=Next Step C=Challenging

To clarify what these levels mean, take the example "The Dancing Brothers" from How and Why Stories. The level designation that follows it is 3-5=C; 6-8=NS. That means it is a "Challenging" story for third through fifth graders; and a "Next Step" (or medium difficulty) story for sixth through eighth graders. It is not listed for second graders which means we feel it is too difficult for the average second grader.

Because we recognize that the teacher's goal will often be for older students to tell the tales to younger children, we have included levels through eighth grade. (This does NOT mean that the stories are not appropriate for telling by high school students or by adults; the levels for younger students will help any teller have a sense of the difficulty level of the story.) Be sure to explain that the stories your students choose must be at the level of the younger students so the children will be able to understand and enjoy them.

Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom

The Argument Between the Sea and the Sky (Phillipines) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

The Belly (Greece/Aesop) 2=NS; 3-8=S

The Boy Who Turned Himself into a Peanut (Democratic Republic of Congo) 2=NS; 3-8=S

Coyote and the Money Tree (Native American/Apache) 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

The Dog and His Reflection (Greece/Aesop) 2-8=S

Excuses, Excuses (Greece/Aesop) 2=NS; 3-8=S

The Frog and the Ox (Greece/Aesop) 2=NS; 3-8=S

A Handful of Peanuts (Greece/Aesop) 2-8=S

How Rabbit Fooled Whale and Elephant (U.S./African-American) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

How the Milky Way Came to Be (Iran) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

The Jackal and the Lion (India) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

Juan Bobo and the Pot That Would Not Walk (Mexico) 2-4=C; 5-8=NS

Like Meat Loves Salt (Europe) 2-3=NS; 4-8=S

The Little House (Russia) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

Monkeys to the Rescue (Tibet) 2-3=NS; 4-8=S

The Rat Princess (Japan) 2=C; 3-8=NS

Sneezy (Original story written by a child) 2-8=S

Three Goats in a Turnip Field (Norway) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

Tilly (England, Canada, United States) 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

Two Stubborn Goats on One Narrow Bridge (Cameroon) 2-8=S

The Two Who Tried to Please Everyone (Greece/Aesop) 3-5=NS; 6-8=S

Why Deer and Tiger Fear Each Other (Brazil) 3-8=C

Why Frogs Croak When it Rains (Korea) 2-3=NS; 4-8=S

Why Parrots Only Repeat What People Say (Thailand) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

Wind and Sun (Greece/Aesop) 2-8=S

How and Why Stories: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell

(Little Rock, AR: August House, 1999)

The Dancing Brothers (U.S./Onondaga Indians) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

How Brazilian Beetles Got Their Gorgeous Coats (Brazil) 2-3=C; 4-5=NS; 6-8=S

How Owl Got His Feathers (Puerto Rico) 2=NS; 3-8=S

How Tigers Got Their Stripes (Vietnam) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

The Mill at the Bottom of the Sea (Korea) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

The Quarrel (U.S./Cherokee Indians) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

Rabbit Counts the Crocodiles (Japan) 2-4=NS; 5-8=S

The Story of Arachne (Greece) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

The Straw, the Coal, and the Bean (Germany) 2=C; 3-5=NS; 6-8=S

The Taxi Ride (Mauritania/Northern Ghana) 2-3=NS; 4-8=S

Thunder and Lightning (Nigerio/Ibibio) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

The Turtle Who Couldn't Stop Talking (India) 2=C; 3-5=NS; 6-8=S

Two Brothers, Two Rewards (China/Korea/Japan) 2-4=C; 5-8=NS

Where All Stories Come From (U.S./Seneca Indians) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

Why Ants Are Found Everywhere (Burma) 2=NS; 3-8=S

Why Bat Flies Alone At Night (U.S./Modoc Indians) 2=NS; 3-8=S

Why Bear Has a Stumpy Tail (Norway) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

Why Cats Wash their Paws After Eating (Europe) 2-8=S

Why Dogs Chase Cats (U.S./African-American) 2-3=NS; 4-8=S

Why Frog and Snake Never Play Together (Cameroon/Nigeria-Ekoi) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

Why Hens Scratch in the Dirt (Philippines) 2-3=C; 4-8=NS

Why Parrots Only Repeat What People Say (Thailand) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

Why the Baby Says 'Goo' (U.S./Penobscot Indians) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

Why the Farmer and the Bear Are Enemies (Russia) 2-3=NS; 4-8=S

Why the Sun Comes Up When Rooster Crows (China/Hani) 2-3=C; 4-8=NS

Noodlehead Stories: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell

(Little Rock, AR: August House, 2000)

The Boy Who Sold the Butter (Denmark) 2-3=C; 4-8=NS

Clever Elsie (Germany) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

Dead or Alive? (Uruguay) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

The Donkey Egg (Algeria) 2-3=C; 4-5=NS; 6-8=S

The Farmer Who Was Easily Fooled (Lebanon) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

The Fool's Feather Pillow (Ireland) 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

The Hunter of Java (Indonesia /Java) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

I'd Laugh, Too, If I Weren't Dead (Iceland) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

Juan Bobo and the Pot That Would Not Walk (Puerto Rico) 2-4=C; 5-8=NS

The King Brought Down By One Blow (Philippines) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

The Man Who Didn't Know What Minu Meant (Ghana) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

The Mayor's Golden Shoes (Poland /Jewish) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

The Men With Mixed-Up Feet (Russia) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

Next Time I'll Know What to Do (England) 3-8=C

The Ninny Who Didn't Know Himself (Moldova) 3=NS; 4-8=S

No Doubt About It (Iran) 2=NS; 3-8=S

Scissors (Norway) 3-8=C

Seven Foolish Fishermen (France) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

Such a Silly, Senseless Servant (China) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

What a Bargain! (Arabia) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

When Giufa Guarded the Goldsmith's Door (Italy) 2=NS; 3-8=S

Whose Horse is Whose? (United States/Indiana) 2=NS; 3-8=S

The Wise Fools of Gotham (England) 3-8=C

Stories in my Pocket: Tales Kids Can Tell

(Golden, CO: Fulcrum, 1996)

Bat Plays Ball (Native American/Creek) 2-3=C; 4-8=NS

The Beautiful Dream (Native American/Navajo) 2=NS; 3-8=S

The Biggest Donkey of All (Armenia, Russia, Turkey) 2-3=NS; 4-8=S

The Biggest Lie (Russia) 2-3=NS; 4-8=S

Bracelets (by Laurel Hodgden) 2=C; 3=NS; 4-8=S

The Brave But Foolish Bee (Greece/Aesop) 2=C; 3=NS; 4-8=S

The Bundle of Sticks (Greece/Aesop) 2=NS; 3-8=S

Clytie (Greece) 2-4=C; 5-8=NS

Do They Play Soccer in Heaven? (United States) 3=NS; 4-8=S

The Fox and His Tail (Mexico & Nicaragua) 2=C; 3-8=NS

The Golden Arm (England) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

How Coyote Was the Moon (Native American/Kalispel) 2=C; 3-8=NS

King Midas and the Golden Touch (Greece) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

Master of All Masters (England) 3-8=C

The Mirror That Caused Trouble (Korea) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

The Mouse and the Sausage (France) 2-3=NS; 4-8=S

The Mysterious Box (Scandinavia) 2-8=S

The Night the Moon Fell Into the Well (Turkey) 2=NS; 3-8=S

Oh That's Good! No, That's Bad! (United States) 2-3=NS; 4-8=S

On a Dark and Stormy Night (United States) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

The Paper Bag Princess (by Robert Munsch) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

The Silversmith and the Rich Man (Jewish) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

Skunnee Wundee and the Stone Giant (Native American/Seneca) 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

The Stonecutter (Japan) 3-8=C

Tilly (England, Canada, United States) 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

Wait Till Whalem Balem Comes (African-American) 3-8=C

Who Will Close the Door? (India) 3-8=C

Who Will Fill the House? (Latvia & Lithuania) 2-8=S

Why Anansi the Spider Has a Small Waist (West Africa) 2-4=C; 5-8=NS

Why Crocodile Does Not Eat Hen (Africa/Bantu) 2=C; 3-5=NS; 6-8=S

Through the Grapevine: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell

(Litte Rock, AR: August House, 1999)

Ah-Choo! (Malaysia) 2=C; 3-5=NS; 6-8=S

The Argument Between the Sea and the Sky (Philippines) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

The Baker's Daughter (England) 3-4=C; 5=NS; 6-8=S

The Bell That Knew the Truth (China) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

The Big, Wide-Mouth Frog (U.S.) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

The Blazing Rice Fields (Japan) 3-8=C

The Boy Who Battled the Troublesome Troll (Norway) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

The Emperor's Secret (Serbia) 3-8=C

The Fearsome Monster in Hare's House (Kenya & Tanzania/Masai) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

The Gorilla That Escaped (U.S.) 3=C; 4-5=NS; 6-8=S

The Hero of Holland (Holland) 2=C; 3-5=NS; 6-8=S

It's About to Fall! (Mexico) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

The Jester's Last Trick (Poland) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

Just a Drop of Honey (Burma/Thailand) 3-4=C; 5-8=NS

The King and the Wrestler (India) 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

King of the Birds (Wales) 2-3=C; 4-5=NS; 6-8=S

The Knee-High Man Grows Up (U.S./African-American) 2=C; 3-8=NS

Monkey Gets the Last Laugh (Brazil) 2-3=C; 4-8=NS

One Good Trick Deserves Another (Tibet) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

Rabbit's Riding Horse (Puerto Rico) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

Scrambled Eggs (Denmark) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

The Seal Woman (Iceland) 3-8=C

The Silent Witness (Iran) 2-3=C; 4-8=NS

Sweet or Sour? Greece (Aesop) 2=NS; 3-8=S

The Tail Trade (Canada/Maliseet Indians) 2=C; 3-5=NS; 6-8=S

Taking the Bad with the Good (Congo) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

The Thief Who Aimed to Please (Eastern Europe /Jewish) 3-8=S

Turtle Returns a Favor (Ghana/Ashanti) 3-5=C; 6-8=NS

Watermelons & Walnuts (Turkey) 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

Why Sun & Moon Live in the Sky (Nigeria) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

The Woodcutter and the River Demon (Russia) 2=C; 3-4=NS; 5-8=S

Photocopying Policy for Classroom Use of Our Books

Many teachers and storytellers have asked what is fair regarding photocopying of stories from our books for use by students in a classroom, and have suggested that we spell out a policy. We would like to be generous with our materials because our main goal is to get kids telling and reading stories. We recognize that most schools cannot afford to buy an anthology of stories for each of the students in a classroom where a storytelling project is done. For the many reasons that we outline in Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom (see page 83-85 ), it is far easier to manage a classroom storytelling project, especially with elementary age students, if they choose from individual copies of stories that have been divided into three categories by difficulty level. But that can defeat one of the main purposes of such a project, which is to get students excited about books. However, when students know that the story they chose to tell is from a book that is available in their classroom, they bond with the book and want to read other similar stories in it and other books. Thus we choose to allow photocopying within reason and have described the specifics below.

We make our living as storytellers and authors and need those who use our books to be respectful. There is much confusion about the "fair use" provision of the copyright law. Some educators think that, as long as they are using materials in school with their students, anything is "fair use." For example, one school librarian recently hired us to tell stories at her school. During our break, she took us to the library, showed us piles of stories she had copied from our books, and said, "I'm doing a storytelling unit with third, fourth, and fifth graders. All of your books are just great. I borrowed them from the public library and made copies for all the kids . . . " We were thrilled to hear about her project and, at the same time, dismayed by her interpretation of "fair use." We admit that we didn't fully understand the law until we read it carefully and found that, as the following summary indicates, the rules are quite restrictive:

What the "Fair Use" Provision of the Copyright Law Allows

The "fair use" provision of the U.S. copyright law gives educators the right to reproduce some copyrighted materials, but these reproductions must meet specific guidelines. Basically, the law tries to balance the needs of teachers to use materials with the rights of authors to sell their works. Here are examples of what is and is not considered to be "fair use" for educators in the classroom:

A. It is permitted to make a single copy for each student in a class of a single story from a larger work as long as the story is less than 2,500 words. The copies must be used for classroom use or for discussion, and each copy must include a copyright notice (for example: © 2003 Copyright holder's name, title of book, etc.). However, there are many further restrictions, such as: the same story may not be copied year after year without written permission; not more than one story may be copied from the same author during one class term; and copying cannot be used to create or take the place of anthologies and should not substitute for the purchase of books.

B. It is forbidden to copy a picture book in its entirety. No more than two pages may be copied, and those two pages must not constitute more than ten percent of the entire work.

For more information see United States Copyright Office, Circular 21, Reproduction of Copyrighted Works by Educators and Librarians; Copyright for Schools: A Practical Guide by Carol Sampson, (Worthington, OH: Linworth, 2001); and A Teacher's Guide to Fair Use and Copyright: Modeling Honesty and Resourcefulness by Cathy Newsome, 1997; found on the Web at: http://home.earthlink.net/~cnew/research.htm#Fair%20Use%20Matrix%20for%20Teachers.

Here are the guidelines that we would like schools to follow if they use our books in classrooms:

Photocopying/Internet Policy for Teachers

What is Permissible:

1. If there is a minimum of one copy of one of our anthologies (Children Tell Stories, Stories in My Pocket, How and Why Stories, Noodlehead Stories, and Through the Grapevine) in the classroom, we give a teacher permission to copy stories from that anthology when putting together a pool from which students choose. Once a student chooses a particular story, it is permissible to make a school copy and a home copy for the child. A copyright notice must be included on any story or handout that is copied. For example: Copyright 1999 Martha Hamilton and Mitch Weiss, How and Why Stories: World Tales Kids Can Read and Tell. Little Rock, AR: August House Publishers. All rights reserved. (Note that to copy from all of our anthologies you must have a minimum of one copy of each anthology in your classroom.)

2. You may post one quote OR one exercise of not more than 300 words from any of our books on an Internet site, as long as proper credit is given. If you wish to post more, you must ask permission.

What is NOT Permissible:

1. It is not permissible to have one copy of a book in the school library and copy and use the stories in many classrooms. Multiple copies are available at a discount price from us or the publishers.

2. It is not permissible to copy our picture books. Note that some of our trade picture books (for example, The Hidden Feast (August House 2006) will have a shorter, more kid-friendly, tellable version posted on our Web site that teachers can download and use in their classrooms.

The inexpensive paperback picture books we have written as part of the "Books for Young Learners" series from Richard Owen Publishers will make it easier for teachers because these are individual books; no photocopying will be needed (and none is permitted). Richard Owen Publishers plans to publish four to six of our stories as part of this series each year. Eventually there will be a critical mass of these books which will make it much easier for teachers of younger students to lead a storytelling unit where each child tells a different folktale that is short and simple.

3. It is not legal or permissible to take one of our forms, handouts, exercises, or stories, adapt it slightly, and then post the information on the Internet or publish it in a book as your own. That is plagiarism.

4. The handouts and stories in Children Tell Stories may be copied by teachers who own the book for use in their classrooms. Photocopying them for other teachers or posting them on the Internet is an infringement of copyright.

5. Use the exercises in Children Tell Stories or Stories in My Pocket in any teaching situation as long as you give proper credit. You have permission to photocopy one exercise as a sample (no longer than what fits on one page without asking our permission) if you are sure to put the full copyright information on the page. You also have permission to copy the page on state standards (page 14) for educators. (This does NOT mean that any of these items can be posted on the Internet!)

6. It is not permissible to post an audio or visual image of a child telling one of the stories in our books (with the same title and just a few words changed here and there) without proper credit and without our permission. Although the story may be an old folktale, the particular version is copyrighted by us.

Photocopying Policy for Storytellers

It is permissible for storytellers to use our books in teaching storytelling in classrooms as long as the above as well as these additional rules are followed:

A minimum of one copy of any book from which stories are copied must be bought for each classroom in which the storyteller works. This cost must be built into the cost of a storytelling residency. (For example, if the storyteller teaches storytelling in five third grade classrooms at a particular school, and uses stories from Children Tell Stories and Stories in My Pocket, the school needs to purchase five copies of each book, one for each classroom.)

A Note on the Stories That Students Choose from in the Companion DVD to Children Tell Stories: Teaching and Using Storytelling in the Classroom

The photocopies of stories from which you see students choosing in the companion DVD are all folktales we have retold or stories we have written. Some have already been published in various books; others we have retold more recently and have not yet been published. Hearing many children tell a story helps us immensely in the editing process. Continually revising and updating our versions of the tales assures that the stories we present to children are truly "tellable" by them.